"On this perfect day, when everything has become ripe and not only

the grapes are growing brown, a ray of sunlight has fallen on to my life:

I looked behind me. I looked before me, never have I seen so many and such

good things together."

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE-ECCE HOMO

VISUAL AWARENESS is not the exclusive preserve of artists. In fact. in some respects visually aware non-artists have an advantage. They can learn from artists, but not having the technical ability to render, they do not feel compelled to represent artistically what they have seen. Such people do not become overly dependent on visual impressions and are free of some of the frustrations that beset artists. For instance, the artist Alberto Giacometti felt he was a failure because he could not completely paint or sculpt what he had seen. The fact that he was world famous was little consolation. Non-artists cannot experience the artist's pleasure in communication, but they can experience their own form of visual creativity. Moreover, the energy derived from intense visual awareness imparts greater freedom and creativity to all of life's activities.

The sculptor Henry Moore said that the main purpose of art is to enhance one's appreciation of the visual world. Many casual as well as sophisticated visitors to art museums are either unaware or unmindful of this statement. Clinging to their own visual prejudices, which bear no more relationship to the richness of reality than a sketch map does to a landscape, they claim either not to understand art (especially "modern" art) or uncritically venerate it. The turgid jargon of some art critics only increases art's remoteness for most people.

There are many good art critics and historians, but I believe, based on my experience, that someone who is truly interested in learning to see from art should go easy on them for awhile. First look at art unmediated by words and theories or as Paul Gauguin said, "Emotion first! Understanding later"

One of the main questions a viewer should ask of an artist is: If I look at your work long and hard, if I meditate on it, trace its form with my eyes' hands, and take in the colors, will it disclose previously unappreciated aspects of the visual world to me? The principle involved seems to be a variation of the sacred/profane distinction discussed by philosophers of religion. Virtually any object displayed in an art museum is automatically sanctified within its confines. Its power is ultimately measured by how much it extends beyond the museum to influence the "profane" world of everyday experience. The greater the artist the greater is his or her ability to break down barriers between the sacred and profane visual worlds.

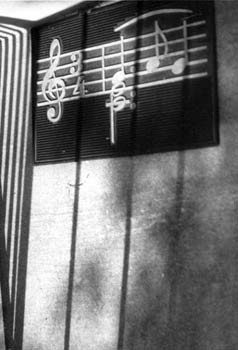

But access to art museums while helpful is not essential. If you can see the strangeness of a random assemblage of ordinary objects temporarily divorced from their utilitarian associations, the beauty of the cracks in the sidewalk, eroded street turn arrows and crosswalks, peeled paint, and the patina of trash cans and other artifacts exposed to weathering: if you can prize the mystery of leafy reflections on street signs, of objects distributed in space, see shadows as more than just projections but as part of the objects themselves and more generally accord equal rights to all visual experiences and not dismiss them as mere shadows, reflections, or distortions, then you have gone a long way towards a richer appreciation of the visual world.

In March 1985, I visited Bill Stark, a friend who lived in Eugene, Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest. We spent several days walking around the town. He suggested I write something about visual awareness. I declined because I feared that my prose would not be up to the task. But the next year when I returned to Eugene, Bill again suggested that I write and my visual vocabulary having expanded considerably, I decided to give it a try. I began writing soon after arriving back home in Washington, D.C., and I also began keeping a daily journal. This book is the product of my experience with an awakening visual awareness, and the words are an attempt to share with and possibly instruct others in the creative experience of developing visual imagination.

This is not intended to be read as literature. Nor does it seek to promote any particular way of life, despite my occasional use of words from eastern religions. This is a manual of visual awareness as I have experienced it. It may stimulate readers to become more conscious of their environments but not necessarily in the way that I have developed such an awareness. The important thing is to teach yourself. If this guide shows some readers the potential benefits of visual awareness, which they must develop in their own way, it will have accomplished its purpose. The Chinese speak about the "ten thousand things" to be seen. There are also ten thousand ways in which to see them.

Part I reflects on the essence of Vision-Light. Each of us sees light differently according to our own imagination and experience. This section attempts to demonstrate how a loving attention to light can stimulate imagination and enrich experience.

Part II presents a new vocabulary for experiencing the rhythm and dance of objects in motion and for extending one's awareness of light and imagery.

"Excerpts from a Word Sketchbook" provides the narrative framework for Parts III through V, with photographic studies entitled "Imagination," "Humor," and "Streetwise." The sketchbook is derived from my daily journal and is a spontaneous, virtually unedited record of visual experiences. They may seem excessive or overwhelming to some readers. You may want to read the excerpts quickly or the first time and then refer back to them as you develop your own sense of visual awareness.

The photographs included as studies were taken between January and December of 1987. They are arranged into the five groups which depict light, rhythm, imagination. humor, and "streetwise," respectively.

I would like to thank Leonard Yoritomo for lending me his dark room equipment and instructing me in its use and Bill Stark for encouraging me to continue with this new hobby.

DENNIS ROTH

Copyright 1990 & 2000 by Dennis Roth - Please do not distribute without the author's permission.